By: Elizabeth Linda Yuliani, Carol J. Pierce Colfer, Amy Ickowitz, Valentinus Heri, Hasantoha Adnan

It was the early 2000s. We were conducting baseline studies, including an assessment of gender-differentiated daily roles, in a remote village for a project in Jambi Province, Indonesia. When the conversation turned to cooking, some men quickly said, “Cooking is definitely a woman’s role. If a man ever have ‘to go to the kitchen,’ it’s a sign he needs to find a new wife.” They laughed as if joking. Other men nodded in agreement, while the women appeared uncomfortable.

In conversations with women, they asked one of the author’s (Yuliani) age. They said, “Ma’am, here in our village, women your age [mid-30s] already have grandchildren.” A young woman explained that girls, including herself, were often forced to marry once they finished primary school (around 14–15 years old).

A similar cultural pattern emerged during baseline studies in South Sulawesi. In conversations with men, they said, “We fully support our wives participating in various activities. We believe it will bring good outcomes. But if they’re busy with life outside the home, they must accept that we, the husbands, might marry another woman to take care of us and the family.”

In these locations, women attended meetings but participated passively. When one or two women voiced their opinions, men participants often made fun of them. This embarrassed the women and discouraged them from speaking further.

We observed a contrasting situation in Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan. Also in the early 2000s, we saw Iban Dayak and Malay men cooking. When we asked if men were used to cooking, they looked at us and laughed. “Yes, we cook. What’s wrong with it? We are a fishing community. We (men) often stay in floating huts far from home, so we cook our own food,” they explained. In conversations with Iban Dayak families about women’s participation in training or workshops, men said, “We [husband and wife] take care of the family together. My wife is the mother of our children. If she is empowered, so are our children.” In village meetings, women spoke freely—sometimes even taking the lead—and this was seen as normal. Although experiences varied between villages and families, in general, women and men exhibited relatively equal power dynamics.

The first two cases revealed strong social barriers to women’s meaningful participation. Throughout the project period, we sought to address these challenges by applying gender-sensitive, gender-responsive, gender-empowerment and gender-transformative approaches iteratively. However, because such social norms are deeply embedded, they are difficult to shift. What strategies or tools did we use to catalyze change? One particularly effective approach was the daily routine exercise, which significantly altered men’s perceptions of gender roles and equity.

In separate groups, men and women were asked to draw a clock and describe their daily routines. The results were striking: men spent about five hours a day working in the field, with several breaks for coffee, smoking, and chatting. Women, on the other hand, spent more than twice that time preparing meals, collecting firewood and water, caring for children, washing clothes, and tending crops. Men were surprised by the unequal workloads. They became more open to supporting women’s participation and began sharing household responsibilities more equally.

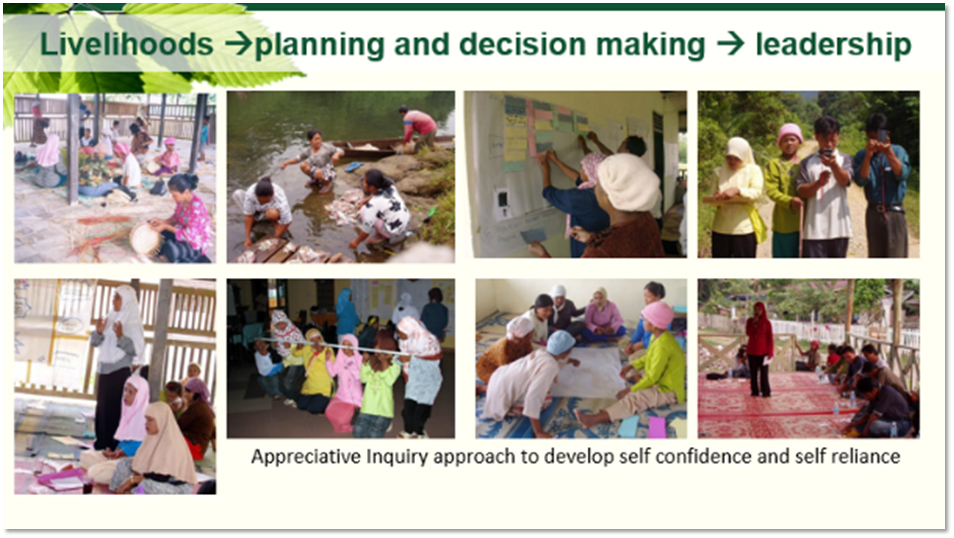

The project team built on this shift by strengthening women’s capacities in areas such as non-timber forest product (NTFP) production and marketing, village planning and decision-making, participatory boundary mapping, and leadership.

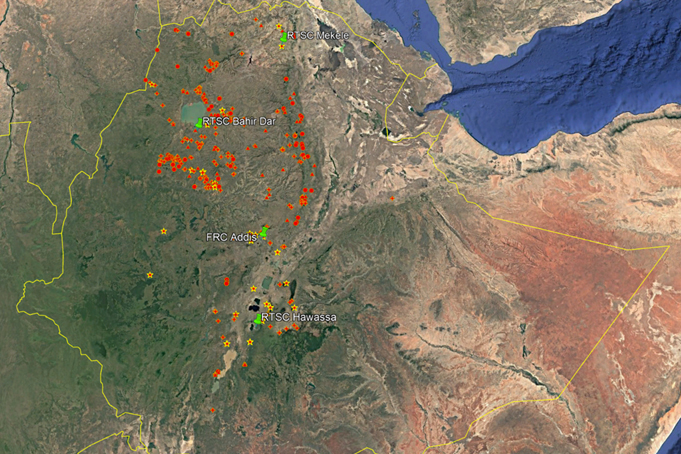

In Kapuas Hulu, particularly among Iban Dayak communities, the GESI situation was markedly better than in the other two sites (Colfer et al., 1999). The underlying causes of inequality there were mainly structural—such as lack of electricity and limited opportunities for women to build their skills and agency (Yuliani et al., forthcoming). In this context, we applied gender-empowerment approaches rather than transformative ones. We understand empowerment as expanding women’s capabilities, whereas transformation seeks to alter fundamental relationships between men and women (or other social groups). Among the Iban, there was little need for such a fundamental shift.

Different groups have different needs. To achieve GESI, we must tailor our approaches to each context and focus on identifying the strengths of the people we work with. This allows them to engage more meaningfully in planning and decision-making processes. Such efforts must be grounded in a solid understanding of their preferences, interests, and needs.

A crucial role for outsiders is to help build local capacities, ensuring that communities have sufficient access to information, knowledge, and options—including the risks and benefits—before making informed decisions.